The origin of the Pedi People is traceable to the Tswana-speaking Kgatla offshoot of the Proto-Sotho people who migrated from East Africa to settle in South Africa. The Pedi tribe is distinguished with the language known as Sepedi, also referred to as BaPedi. Like several other African tribes of similar ilk, they practice their own version of the African traditional religion which is rooted in the power of the ancestors, the efficacy of the diviners, and their Malopo rituals; these are considered to be of great significance in the tribe.

The Pedi people also follow their own cultural practices where the man is regarded as the head of the family. At puberty, young men and women are expected to go through the initiation process, and when the time comes for marriage, the elders will undertake the responsibility of finding a befitting partner for their nubile men and women.

The Pedi People Owe Their Origin to the Tswana-speaking Kgatla Offshoot of Proto-Sotho People

Proto-Sotho people are said to have migrated south from the East African great lake region, making their way alongside modern-day western Zimbabwe. They passed through successive waves spanning five centuries with the last cluster of Sotho speakers known as the Hurutse, putting down roots in the western region of Gauteng; this happened around the 16th century.

Pedi/Maroteng owes its origin to this group, the Tswana-speaking Kgatla offshoot. Around 1650, they put down roots in the region to the southern part of the Steelpoort River. Over several generations, cultural and linguistic homogeneity developed to an extent. They continued existing in the area till the last half of the eighteenth century when they deemed it necessary to break new frontiers, broadening their influence over the region. This led to the establishment of the Pedi paramountcy; this was achieved by bringing the smaller chiefdoms in the neighborhood under their control.

A lot of migration took place in and around the area and was marked by groups and clusters from diverse ethnicity coming to concentrate around dikgoro (ruling nuclear groups). These groups identified themselves via symbolic allegiances to totemic animals like tau (lion), kwena (crocodile), and kolobe (pig).

Struggle for Control within the Pedi Kingdom

King Thulare ruled the Pedi People from c. 1780–1820 under a polity consisting of land that spanned from present-day Rustenburg down to the Lowveld (west) and as further south to the Vaal River. The South East Ndwandwe invaders did a good job of undermining Pedi power during the Mfecane. This was followed by a period of dislocation following which Thulare’s son, Sekwati, re-stabilized the polity.

After Sekwati succeeded his father as the Pedi People’s paramount chief in the northern Transvaal (the present-day Limpopo), he had frequent clashes with the Matabele under the leadership of Mzilikazi. Also, the Swazi and the Zulu plundered them, and as if that was not enough, Sekwati had to face numerous struggles, leading to negotiations for control over labor and land, and with the Boers (the Afrikaans-speaking farmers) who had also settled in the region.

These land disputes occurred in 1845 after Ohrigstad was founded. However, in 1857, the town was later incorporated into the Transvaal Republic leading to the formation of the Republic of Lydenburg. It was during this time that they reached an agreement that the border between the Republic and the Pedi people was the Steelpoort River.

Two Sides of the Story About the BaPedi People and Northern Sotho (Basotho ba Lebowa)

You can find the Pedi people in Limpopo, SA’s northeastern province, and some areas in Mpumalanga where a majority of them have settled down. But there has always been confusion about who they really are. It has always been hard to distinguish the BaPedi people from the Basotho ba Lebowa or the Northern Sotho.

One military version of the story said that, at a point, the BaPedi people became very powerful under a powerful and influential king whose kingdom comprises a large piece of land. This was when the BaPedi had a powerful army that conquered smaller tribes, proclaiming dominance over them.

There is another explanation that said that after one of the BaPedi kingdoms declined, some tribes that got seceded from the kingdom began using the term, Northern Sotho.

- The Pedi People are of Tswana origin

- They descended from Kgatla (Bakgatla) – a Tswana-speaking clan which around the 1700s migrated to ‘Bopedi’; this is the present-day Limpopo.

- The Pedi heartland is called Sekhukhuneland, situated between the Steelpoort River and Olifants; these are also known as the Tubatse and the Lepelle.

- The Pedi became the first among Sotho-Tswana peoples to be referred to as Basotho.

- Derived from uku shunta (Swazi word), Basotho refers to the clothing style of the Pedi people who took the moniker with pride. Before long, similar tribes started seeing themselves as Sothos.

They are Speakers of Sepedi and BaPedi Language

Northern Sotho (Sesotho sa Leboa) is one of SA’s 11 official languages. It constitutes about 30 distinct dialects, and one of them happens to be Pedi. There has been much confusion around the term, Sepedi, (the Pedi people’s language), which has always been referred to as Northern Sotho, however, this is incorrect. This confusion is said to have occurred because the missionaries who took the credit for the development of the orthography used for Northern Sotho came into contact with the Pedi tribe. With that said, Northern Sotho (Sesotho sa Leboa) has never been the same thing as Sepedi. Sepedi which is also called BaPedi is the language spoken by the Pedi people.

Closely related to Sepedi are the official language of Tswana or Setswana, the dialect of Setlokwa and the interconnected Sotho language, and Sesotho sa Borwa (Southern Sotho).

You will get a majority of speakers of Sepedi in the northern region of SA; this includes Limpopo, the provinces of Mpumalanga, the North West province, and Gauteng.

Pedi’s Religious Beliefs Are Not Any Different From What Is Obtainable From Other African Tribes

The Pedi People are not far removed from other known African tribes with respect to their religious beliefs. They believe in the creator and supreme being who is recognized as Modimo/Mmopi. In the African religion parlance, no one can have direct contact or communication with the almighty God and still remain the same. Thus, in the olden days, Africans related to God through their ancestors. To communicate with the ancestors, the Pedi people call on them through the use of a process that involves making offerings, burning incense, and talking to them (go phasa). When the need arises, the people offer animal sacrifices or presentation of beer, the ‘shades’; this can be done on both sides of a person’s family (the father and mother’s side). The chief figure for this family ritual was usually the kgadi (the father’s elder sister is the one that fills this position)

The Diviners In the Tribe are Known as Ngaka

In ancient times, the position of the diviners (ngaka) among the Pedi people was inherited patrilineally. However, in recent times, this particular inheritance is bestowed on a woman through the person’s paternal grandfather or great-grandfather. Under normal circumstances, the position of ngaka manifested through a violent spirit (malopo) possession or serious ailment. When this happens, the suffer cannot find a solution to their issues until they obey the call and train as a diviner. The chiefs in the Pedi kingdom were the ones that functioned as rainmakers for their subjects.

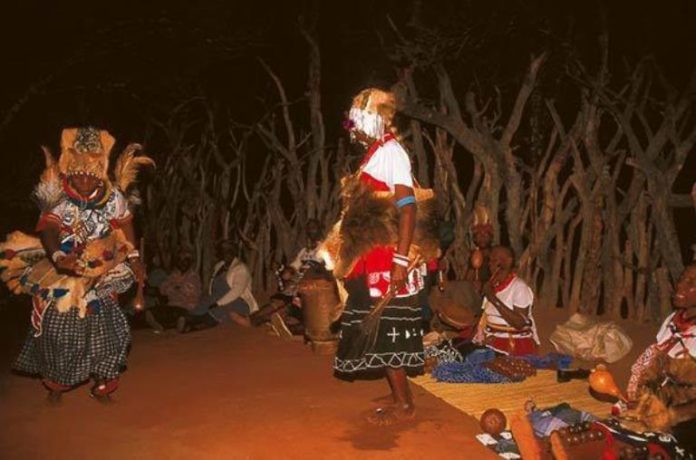

The Malopo Ritual and the Malopo Dance

In the Bapedi tribe, they perform the Malopo ritual which happens to be the ritual of understanding their culture; this is usually accompanied by the Malopo dance. The people generally referred to it as phasa. During the ritual, there is the presentation of beer and animal sacrifice administrated by the key family member, the Kgadi. While some members of the tribe would prefer slaughtering cows and coats as a means of communicating with their ancestral spirit, others would leverage the African traditional beer (tlhotlwa) or even snuff. The people believe that their ancestors can come to them through spiritual power. In the case of a sick person, the ancestral spirit can give him or her strength to heal through bones (ditaola)

The Role of the Malopo Ritual and its Dance Performance

There are several reasons why the traditional healers perform the Malopo ritual and the accompanying dance

- The chief reason for the ritual and dance is to communicate with the ancestral spirit

- The Malopo ritual is aimed at enriching the people’s social and personal lives

- It enables members of the community to inherit their traditional music

- When the Pedi people learn to play the malopo music, it exposes them to teachings on skills as well as appropriate perspectives. They will also imbibe social behaviors. Here, the tradition and culture which encompasses the instrumental techniques, the repertoire of tunes, ensemble procedures, including expectations of decorum and conduct recreate the context it requires for both performance and pedagogy.

- The malopo ritual specifically binds people together; the accompanying music is basically an ethnic bond.

- The music serves as the people’s indigenous knowledge system – the reflection and expression of the Pedi culture as the value and essence of their customs is embedded in its content, roles, and process.

- Through the malopo music, the people re-live the past, savor the present and project the past

- The dance process is a manifestation of the lifestyle and aspirations of the Pedi community.

- The music effectively broadcast the people’s existence, nature, and world views

- The Malopo ritual helps the people in practicing their culture’s socially significant occupations

- The teaching and learning of the Malopo ritual dance; reveals the people’s values

- There are several revealing information in the content of the dance ritual that says a lot about the people’s interest and identity.

- The inherent process does a good job of exposing the ways of the community.

With all that said, it is glaring that the Malopo ritual is the perfect medium for understanding the culture and tradition of the Pedi people. Though modernization made efforts in eradicating some African traditional practices with its impact, the malopo ritual of the Pedi community seems to have survived. To date, the Bapedi still practice it as a means of reflecting on the past, perceiving the presents, and projecting into the future.

Tradition and Culture of the Pedi Tribe

As a people, the Pedi people have always been one with tradition and they follow it to the letter. Some of their ancient traditions like initiation ceremonies for adolescent boys and girls are still practiced to date.

Initiation Ceremonies

The Pedi people differentiate the lives of male and female children by a very important ritual known as initiation. This ritual is carried out as both sexes approach adolescent age.

Initiation Ceremony for Boys

The Pedi refer to boys as bašemane but later mašoboro. The bašemane would spend their youthful days at remote outposts herding cattle alongside their peers and older age sets. Koma is the initiation school of the Pedi people which is usually held once every five years. It is an integral part of the initiation process for boys. As the next Koma builds open, all the adolescent boys who are deemed ready for initiation will be getting prepared for the big day.

While undergoing the initiation process, the youth will be socialized into regiments or groups known as mephato. Each mephato has a leader and the regiment bears his name. Throughout their lifetime, the members of each group will remain loyal to each other. Oftentimes, they travel as a group to work in the mines or in farmlands.

Initiation Ceremony for Girls

As the males are undergoing their initiation processes, the girls are not left out as they will equally get busy with their own koma procedures; However, the records said that the Koma process for girls comes a couple of years after the boys have finished with their own initiation school. The same procedures that apply to the boys are equally obtainable with the girls. They will also be divided into groups.

To date, the Pedi people still practice their initiation rituals and it is licensed by the chiefs for a fee which is a substantial means of income to them. In recent times, the process has been hijacked by private entrepreneurs through the establishment of initiation schools outside the jurisdiction of the traditional Pedi chiefs.

Burial Rites of the Pedi People

Pedi people do not bury their dead immediately after passing. They give the grace of seven days from the time of the person’s demise; this is to give relatives ample time to make arrangements for the burial. The burial arrangements include informing friends, relatives, and every other person that needs to know about the passing.

Informing the deceased friends and relatives on time will afford them the needed opportunity to equally prepare to attend the burial. On the eve of the burial, the tradition of the Pedi people demands that the corpse be covered with cow skin and displayed for friends and family members to come and pay their last respects. This procedure is referred to as go tlhoboga in the Pedi parlance.

By sunrise, the next day, the preparation for the burial ceremony will commence and during the day, the deceased will be committed to mother earth.

Burial Ceremony for Chiefs

Because of the exalted position they held during their lifetime, those who held chieftaincy titles among the Pedi community are not buried in the same way as commoners. Both the burial process and the ensuing ceremony vary. According to the records. A chief does not go to the afterlife alone, at least, two of his councilors will be buried with him. However, it is not stated whether these councilors will be committed to mother earth alive or dead. Perhaps, this is the reason why a chief’s demise is usually shrouded in secrecy for several months even after the person has been buried.

Kinship

The subdivision of chiefdoms and villages within the Pedi community is known as Kgoro and it comprises kinsmen with related men at the center. The kgoro was also regarded as jural and kinship units and there is kgoro-head (dikgoro) whose authority includes the acceptance of people into their units; this was not just determined by relations or blood ties. The dikgoro will eventually face subdivisions when the time comes for sons to compete for authority.

Use of Totems

All Sotho-Tswana groups make use of totems in identifying kinship and sister clans, and the Pedi people are not any different. These are the totems popularly used in Sepedi

- Kolobe (pig)

- Tau (lion)

- Kwena (crocodile)

- Noko (porcupine)

- Kgabo (monkey)

- Phuthi (buck)

- Tlou (elephant)

- Nare (buffalo, and many more.

Inheritance Within The Tribe

In any polygamous household, it is that eldest son that inherits the property of the mother, including the cattle. He is equally left with the task of acting as a custodian to the rest of his family members. However, after the Pedi people experience a massive decline in cattle rearing, including increases in land shortage, they deemed it necessary to alter the system of inheritance, leaving primary land for the last child to inherit.

The Patrilocal Nature of Marriage Among The Pedi

The institution of marriage was patrilocal in the traditional Pedi society and those who have a higher status like chiefs can afford to practice polygyny. In the ruling dynasty, it was preferred for cousins to inter-marry as this is a way of ensuring a degree of political control and integration. Marriage is approved between a man and his mother’s brother’s daughter. This is so because both in-laws on the bride and groom’s sides have blood ties and as such, the bohadi (the bridewealth) will then be utilized in paying further bohadi, all within the confines of the ruling family.

For instance, the bridewealth received from a daughter’s marriage can in turn be used for sponsoring Bohadi when her brother is ready to get married. The favored brother would then repay his sister when the time is right by offering one of his daughters to her son, and they continue keeping it in the family.

The Pedi people’s paramountcy’s power was also cemented by the chiefs of lesser villages, or kgoro, taking their principal (this can be the first wife) wives from the ruling house. This intermarriage system among cousins gave rise to the continuation of marriage links between the subordinate groups and the ruling house. It also involved the payment of extravagant bohadi, majorly cattle, to the Maroteng house.

The Pedi Marriage Process

When the time is considered right for a Pedi man or woman to take a bride/husband, the onus is on the elders to put heads together and select a befitting bride for their son and vice versa. If the nubile young man or woman already has a love interest in the village, the elders will visit the family for introduction and the discussion of marriage proceedings. Subsequently, the two families will make arrangements on when and how to meet.

The parents of the girl would then take a decision on the number of cows or money to be paid as Bohadi. Once the bridewealth exchanges hands, the duo will be considered married and can be together. The onus lies on the younger brother of a dead man to marry his widow to support and care for the children.

Among the Pedi people, a pregnant woman who is due for delivery will need to go to her birth family to give birth and on her return to her matrimonial home, a feast will ensue to which the woman’s family will contribute beer and meat. Once a bride becomes a first-time mother, she will be entitled to her own hut which will be built by her husband.

When the village chief has a newborn baby, the commoners will visit the moshate (royal house) where they will present the newborn with presents and wish it well. After the birth, the chief’s servant will announce the impending feast for the child where there will be merrymaking and a lot of traditionally prepared food.

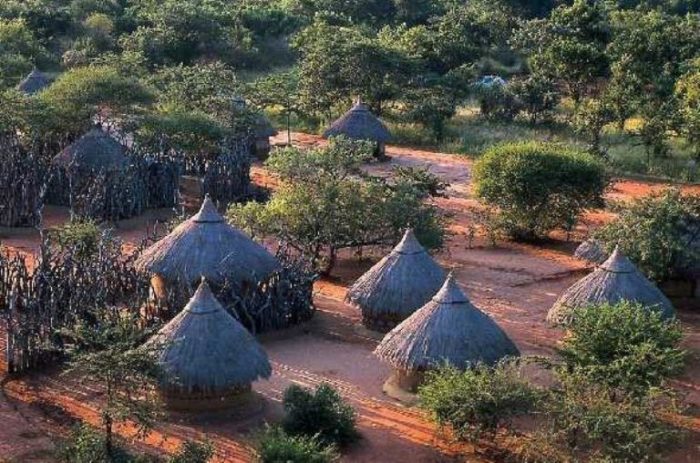

The Tribe Built their Settlements on Elevated Sites

Prior to the period of conquests, the Pedi people settled in relatively large villages and they found their best spots on elevated sites for obvious reasons. Divided into kgoro (plural dikgoro, groups centered on agnatic family assemblage (agnatic means from the father’s side). Each of the kgoro is a collection of households living in huts constructed around one central area. This focal area has several significances – it can function as a meeting place where the members of the cluster gather to resolve burning issues, it can be a graveyard, a cattle byre, or an ancestral shrine.

The residential units of the Pedi people come in the form of semi-circle residential clusters of dwellings and aside from the major residents who have blood ties, the Kgoro can also accommodate other people. The kgoro is usually established by an important son of the chief (kgosi) who serves as the overall judicial and executive authority.

The huts in every household must be ranked in order of seniority. In a polygamous family, the senior wife is entitled to her own thatched hut (these huts are usually round) linked to other huts via a chain of open-air enclosures known as lapa; these are encircled by mud walls.

The older girls and boys in a family will be housed in separate accommodations respectively; these huts are referred to as ‘age sets’ which was regarded as an essential element in the social hierarchy of the Pedi people

Aspiring to inhibit a more modern style of dwelling, along with being practical, the families of Pedi community were led to jettison their round-styled huts for the more sensible rectangular, flat-tin-roofed houses.

House Construction in the Pedi Community

The round-styled huts inhabited by the members of the Pedi communities are called rondawels. The construction of rondawels is a simple process that involves mixing clay with cow dung (boloko). The addition of the boloko is believed to further strengthen the clay which will then be used in molding the walls.

When the walls of the rondawels have been molded to the roofing level, the builders will go into the bust to gather a particular grass known as loala. The loala which is very long and strong will be packed into bangles and used in roofing the rondawels.

Even though their materials and methods were deemed to be rather primitive, the end result of their construction work provided the Pedii people accommodation for centuries, shielding them from the ravages of the sun and rain.

Mmino wa Setšo (music)

Mmino wa Setšo is the name for traditional Pedi music, lit. music of origin. Consisting of a six-note scale, this genre of music was previously played on a dipela (this is a plucked reed instrument). However, the present-day musicians now leverage trade-store instruments like the Jewis harp, including the autoharp (harepa) of the German. Though they were not previously part of the people’s culture, these instruments are now viewed as characteristically Pedi.

Migrants which were influenced by Kibala music entailed re-producing harmonious sounds by playing aluminum pipes that come in different heights. The women go down on their knees to perform the Mmino wa Setšo accompanied by lead singer, backing vocals, and of course the drums. They usually appear topless from their upper torso, shaking vigorously while kneeling.

The Pedi people don’t just sing and dance during merriments, they also love to burst out in songs while at work. There is this belief that singing while working will get the job done faster. They have this popular song about killing a lion to come into manhood. However, this act has since gone into extinction. In those days, a boy who successfully kills a lion will be bestowed with high status; the ultimate prize is getting the chief’s daughter for a wife.

Music in the Pedi kingdom comes in different types played by different categories of people

- Mpepetlwane – This type of traditional music is played by young girls

- Mmatšhidi: Older men and women are the ones expected to play the Mmatšhidi.

- Kiba / Dinaka: Previously played the male folks (both men and boys), women now join in the playing of the Kiba / Dinaka.

- Dipela – this genre of Pedi music is played by everyone

- Makgakgasa – played by older women.

Categories of Mmino wa Setšo and How They are Performed

In the Limpopo region of South Africa, Mmino wa Setšo comes under several categories and each is distinguished by the particular function it serves in the community

Dinaka/Kiba

The peak of Pedi, musical expression is debatably the kiba genre; this has already surpassed its rural roots to emerge as a migrant style. The men’s version of the genre features a band of players, with each instrumentalist playing a metal end-blown pipe of a diverse pitch (this is known as naka, pl. dinaka). Together, this ensemble creates a descending melody mimicking traditional vocal tracks with richly harmonized qualities.

Mapaya provided for a comprehensive evocative examination of Dinaka/Kiba dance and music from the perspective of Northern Sotho

Alternative to Dinaka/Kiba

This is the women’s version which is an improvement on earlier female genres that was recently included in the classification of kiba – a group of female folks who sings songs (koša ya dikhuru- this loosely translates to knee-dance music). The roots of this translation lie in the traditional kneeling dance involving sensational shaking movements of the women’s breasts accompanied by chants. There is always a lead singer, a meropa (an ensemble of drums), and the chorus. The then drums were wood-processed but the present-day drums are constructed from oil drums and milk-urns. You will hear this kind of chant at wedding celebrations or drinking parties.

Mmino wa bana

This category is for children who inhabit an exceptionally special place within the broader class of Mmino wa Setšo. According to research, mmino wa bana can be scrutinized for its educational validity, musicological elements, including the general social functions

Pedi Food Cuisine Includes Both Solid Food and the Local Beer

The Pedi community has its own traditional food which is exclusive to the tribe. In addition to these nutritious edibles, the people also possess the skills of making their own local beer which makes life more enjoyable.

The Tribe members Consume A Variety Of Food

The food consumed by the population of Pedi community ranges from fruits to veggies, beef, carbs, proteins, worms, and the likes. These are some of their popular dishes

- Thophi – This Pedi delicacy is made from mixing maize meal with a fruit known as lerotse; this comes in the form of a melon

- Mashotja – They may not look good to an outsider but these Mopani worms are enjoyed by the Pedi people

- Moroga wa dikgopana – This comes in the form of spinach which after cooking, is molded into rounded shapes and kept to dry under the sun.

- Dikgobe – This is coarsely ground corn/samp with beans.

- Thir diet also inclides Bogobe ba mabele, samp, and maswi (milk). There’s also fruits and veggies like machilo and milo.

Cooking in the Pedi tribe is an exclusive reserve of the women. They cook their family meals on the ground in a three-legged pot with firewood.

Traditional Beer is Brewed From Sorghum

The traditional beer of the Pedi people is made using different kinds of sorghum meals. This is called mabele in the people’s parlance. They mix the mabele with hot water and the mixture will be stored in a cool place; this usually comes in the form of a DIY traditional house constructed out of tree branches.

It takes a while for the beer to be ready and when it is brought out, the old women will proceed to brew it. The ready-to-drink beer will be poured out into muddy pots (moeta) and it will be ready to be served to the elders. The elders would not usually drink their beer from the regular cups, rather, they use traditional cups known as mokgopu.

While the elders in the Pedi community can enjoy the traditional beer at any time, others only get to enjoy this privilege at occasions such as weddings and ancestral ceremonies.

Pedi Traditional Attires For Men

During the period of pre-colonial Africa, the Pedi people were just like every other tribe in the black continent who leveraged different kinds of animal skin for making their garments. The kind of animal skin that goes into the makings of a man’s clothing is an indication of his status in society. You would see the royals putting on lion-skin or leopard-skin processed apparel as a symbol of leadership and to show that he comes from the moshate (the ruling house)

The commoners wear clothes made from the skin of domestic animals like cows, sheep, goats, and the likes. Part of the traditional attire for Pedi men also includes kilts. How they started wearing these kilts is still a mystery but we know that kilts are the traditional skirts worn by Scottish men. Though the Pedi has a few folklores about these male skirts.

Pedi Traditional Attires For Women

The olden days’ traditional attires for SePedi women include a simple front apron called ntepa and lebole (back aprons) processed from strips of animal skin. Though you won’t catch a glimpse of the ntepa and lebole in modern times, modernized clothes with waistcoats that are close in resemblance to these aprons abound. There is also the inner fabric (hele) tied to the waist and another piece of fabric tied onto the top of the apparel called metsheka, matching the moruka head accessory. Doeks is a type of headscarf worn by Pedi women.

Just like the Ndebele, the Pedi people are equally renowned for designs, beadwork, and rich colors. What Pedi women wear varies and can go from long voluminous dresses to calf-length skirts, and pleated blouses. Most of their clothing is accompanied by beadwork and some of their regular designs include embroidery, pleats, and ribbon trimmings.

Artwork Within The Pedi Community Include Pottery, Woodwork, and the Likes

The Pedi People are also remarkable artistic as they have a long history of creative arts which was expressed in the makings of designs and objects. Metal-smithing was one of the most common practices in settlements occupied by the tribe. Apart from bead which was equally a major practice, the people were excellent potters, the evidence of their woodwork was good and they made strong and durable drums. When the Pedi people finish their house construction, they don’t leave the walls plain but paint them in beautiful colors and designs.

Subsistence and Economy

Rainfall can be fairly low in Pedi settlement, but the people still manage to cultivate crops like maize, sorghum, wheat, beans, legumes, pumpkin, and millet. The rear a remarkable number of livestock including cattle, sheep, goat, and poultry. The cultivation of these crops was done by their female folks on land allocated to them at the instance of marriage. It was the duty of women to till the land, do pottery, produce baskets, sleeping mats, build huts as well as decorate them. Their other responsibilities include grinding grains, cooking, brewing, fetching firewood as well as water.

Men may only surface in the farmland during peak times, but majorly, they concentrate on herding the livestock, hunting for prey, and preparing the animal skin. Other masculine duties include woodwork, metal workers, and smiths. The tribe is known to carry out major work communally by work parties known as matsema.

Apart from being a source of sustenance, cattle had a very important role among the Pedi People – it served as a very important status symbol among their male folks and is the main item for the payment of bohadi or bridewealth.

War Tactics of the Pedi People

The Pedi people were hardly a warlike tribe, and no records of them going to fight battles exists. However, according to their customs, they send out their men to opposing tribes to go and sell beads or for divination, but those men were in actual fact, spies who were sent with the mandate to spy the land and report any opportunity for the Pedi tribe to wage an attack on their kraal.

When an opportunity for an attack is spied out, the chief would assembly all the able-bodied men with their weapons consisting of battle-axes and assegais. The men will also equip themselves with sustenance for the duration of the journey. When they are ready for the attack, the Pedi army employs a peculiar tactic that involves moving in the opposite direction to the target, then on the second night, they will suddenly change course and rush towards the targeted kraal.

Their attacks were usually conducted stealthily without taking prisoners, save for the female folks and children. Sometimes, bloodshed may result from resistance from the targeted tribe. Compare to the legendary Zulu tribe and the Matabele that took the art of war as a way of life, the Pedi People were primitive in their military organization.

Each Pedi man is expected to provide his needs, and regarding the course of action, he can follow his own idea. The onus is on the chief to formulate tactics and assign its execution to one of his brothers. The brother will then assume the role of active command over the others.

After successful looting, all looted cattle will be put in charge of the commander who ensures that it will be shared judiciously – a third goes to the kraal of the chief, a third goes to the slaughter, and the last third will be given to the men who executed the attack. The women and children taken from the opposing tribe are also part of the look and will be shared among the chief’s followers.