The Tswana people who are majorly settled in South Africa and its environs are people with diverse cultural and traditional beliefs. They were originally a Sotho group that broke away to form their own sub-tribe and their demographic distribution still centers around SA. Though the effect of colonialism and civilization is quite extensive within the tribe, the people have proved to be tenacious with their norms and values. This is why they still practice their traditional marriage rites. Some of the tribe members still take ceremonies like naming, coming of age, and initiation very seriously.

What of the religious beliefs of the tribe, it is still very much intact in most regions occupied by the Tswana people. The ngak (healers or diviners) is still believed to have the powers to communicate with the ancestral spirit on behalf of the living. Christianity did try in the eradication of some harsh aspects of their religion but the tribe can still boast of several diviners that still practice their crafts like in the days of old. In fact, the Tswana’s version of Christianity is nothing but a blend of Christian and non-Christian practices, symbols, beliefs, and the likes.

Origin Of The Tswana People

Icon is the name of the Sotho-associated pottery in South Africa that dates back to between 1300 and 1500. As with the Nguni people, linguistic and anthropological data suggest or imply an East African origin for the Sotho-Tswana speakers; this instance is taken from what is now known as Tanzania. By 1500, these Sotho groups had already broken new frontiers, expanding to the west and south and later separated into a total of three clusters. These distinguished groups include:

- The South Sotho – these later became known as the Basuto and Sotho

- The West Sotho – they later became the Tswana

- The North Sotho – these people later came out as the Pedi

However, despite the separation, all three clusters practice similar beliefs, dialects, and social structures. It was only the 19th century difiqane period that established the three groups. The Tswanas by the 16th century found a settlement in what is called the Western Transvaal and they existed under two groups:

- The Tlhaping and Rolong – this group existed under the leadership of the metalworker Chief Morolong

- The Bafokeng – people of the dew.

The Tswana States in Botswana began growing by 1700 after migrants from Hurutshe and Kwena founded what is known as the Ngwaketse chiefdom among the Khalagari-Rolong in the Southeastern part of Botswana. Their mainstay then was cattle rearing, hunting, and copper production.

During the difiqane (Zulu: mfecane) – a period of political disruption, warfare, and migration, the ensuing chaos caused varying degrees of hardship, suffering, political disintegration, impoverishment, forced movement, and death for the Tswana people. This occurred during the first quarter of the 19th century. However, this was when some groups such as the western Tswana chiefdoms strengthened and prospered so much that they were able to incorporate both livestock and refugees.

Within the first twenty years of the 19th century, the Tswana region began experiencing an influx of European missionaries and traders (the British nonconformist sects). They came to trade in feathers, furs, and ivory which proceeds to empower many Tswana chiefs, giving them the needed power to consolidate control and authority over extensive areas. As Afrikaners began to settle in the Transvaal by the middle of the 19th century, the Tswana people began to view them as threats, leading the chiefdoms to fortify themselves by acquiring firearms. That notwithstanding, many Tswana migrated out of the Transvaal, going westward to settle in what is today known as Botswana.

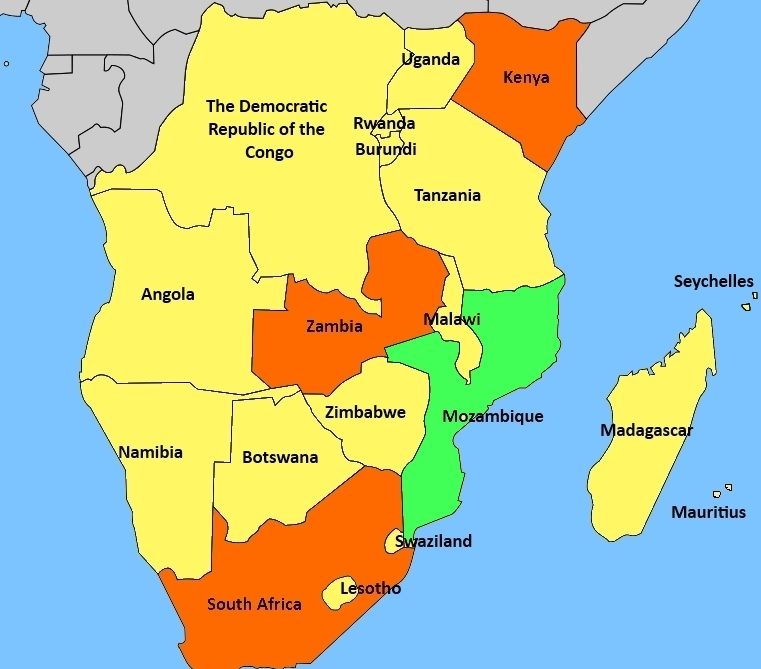

Demographical Distribution of the Tswana People

Southern Africa is home to about four million Tswana people with three million in South Africa and one million in Botswana. Many Tswana indigenes in SA occupy the districts that formed the various subdivisions of their former homeland, Bophuthatswana. They are also found in the neighboring areas of the Northern Cape and the North-West Province. Most urban areas in SA have a lot of Tswana people living in them. You will find the largest number of Tswana people in modern-day South Africa and they are counted among the country’s largest ethnic groups. Also, their language is listed among SA’s 11 official languages.

Bophuthatswana Had 99 Percent of Tswana Speaking People

Bophuthatswana Territorial Authority was created in 1961 and it was later declared a self-governing state in 1972. On the 6th of December 1977, the South African authority granted this homeland independence with its capital sited in Mmabatho. 99 percent of the newly created state were Tswana speaking. By March 1994, they placed Bophuthatswana under two administrators; Job Mokgoro and Tjaart van der Walt. In April 1994, the small, extensive pieces of land got reincorporated into SA. Today, Bophuthatswana forms part of Free State, the North West, Gauteng, and Northern Cape provinces.

The Formation of Dynasties and Tribes of the Tswana People

The British protectorate of Bechuanaland, which is now known as the Republic of Botswana, is named after the people of Tswana. The eight major tribes of the country speak Tswana (also referred to as Setswana). All the dynasties of Tswana people are all related and Motswana (plural Batswana) is the name used to refer to someone who lives in Botswana.

As earlier mentioned, it was during the 17th century that the three major branches of the Tswana tribe came into existence. This became possible after Chief Malope’s sons; Kwena, Ngwaketse, and Ngwato seceded from his chiefdom to establish distinct tribes in Kanye, Molepolole, and Serowe. According to history, their breaking away was informed by drought and expanding populations as they scattered in different directions in search of arable land and richer pastures.

Below is a list of the principal Tswana tribes/dynasties

- Bafokeng

- Bakwena

- Balete

- Bangwato

- BaNgwaketse

- Barolong

- Bataung

- Batlhaping

- Batlôkwa

- Bakgatla

Language Of The Setswana Tribe

The Tswana language is closely related to the Sotho language, besides, both languages are mutually understandable in most areas. Sometimes, Tswana is referred to as Beetjuans, Chuana (Bechuanaland), Cuana, Coana, or Sechuana. Spoken across SA, it is among the country’s recognized 11 official languages. In Botswana, it is regarded as the majority and national language. In 2006, it was established that there were over three million speakers of the Tswana language in South Africa; these people speak it as their home language.

Tswana has pride of place among the first Sotho languages to be written. Heinrich Lictenstein’s text: “Upon the Language of the Beetjuana” in 1806 is among the earliest examples. This was succeeded in 1815 by John Cambell’s “Bootchuana Words and Burchell’s Botswana” released in 1824.

From the London Missionary Society, Dr. Robert Moffat landed in Botswana in the year 1818 to set up the first school in that area. By 1825, the need to write and use Setswana in his teachings became imperative. This led him to start the translation of the holy bible into Tswana. With the advent of 1840, the new testament was already completed and he completed the Old Testament in 1857. Sol D. T. Plaatje happens to be the foremost Motswana who contributed to the writing of Setswana. In 1929, he assisted Professor Jones in writing the publication on “The Tones of Sechuana Nouns”.

Culture and Traditions of the Tswana People

The Tswana people are big on culture and tradition which distinguishes them from neighboring tribes. From childbirth to naming, and coming of age celebrations, the members of the tribe still practice some aspects of these traditions;

Child Birth Has Different Sets of Significance For Baby Boy and Baby Girl

Childbirth has a great significance among the members of the tribe. When the firstborn is a boy, family and relatives are highly excited as the badimo (ancestors) are believed to favor sons more. The essence of having male children is for continuity, thus, a wife that begets a boy is favored while those that have only female children are inviting a second wife into the home.

Naming Ceremony Follows Childbirth

A naming ceremony in the tribe is usually a male affair. If the baby is a boy, they will choose his name from the family lineage. The names below are given to baby boys. They are largely associated with wealth, success, and prosperity to boost their social status

- Mojaboswa – heir

- Kgosietsile – the chief is born or has come

- Mmereki – the worker

- Mmusi – the leader or ruler

- Mokganedi/Modisa – shepherd

For female children, the names are largely associated with domestic activities. Examples include:

- Seapei – the one who cooks

- Khumoetsile – the source of prosperity through bogadi

- Segametsi – this means the one who fetches water

- Seanokeng – meaning the one who fetches firewood

Circumcision Is A Festival of Joy In The Tribe

Among the Tswana people, circumcision is a national ceremony performed between eight to fourteen years of age, even to manhood. The occasion is heralded with feasting and dancing as it is a festival of joy. The girls at the same time will be occupied with their boyali where they will be put under the tutelage of a matron who will initiate them into wifely duties.

Initiations Ceremonies Are Done For Both Sexes

Bogwera is the initiation ceremony for boys while the girls undergo bojale.

Bogwera

This ceremony introduces a boy child into manhood complete with all the expected responsibilities and duties. There, boys are imparted with male deifying social values that strengthen their authority of patriarchal leadership. The supreme right of the full-grown man is introduced to the boys. This confers on them the right to have direct communications with badimo. A man must pass through Bogwera before an honorable marriage can take place.

Bojale

This is exclusively for the girl child as it exposes her to knowledge about family rearing. She will be introduced to her own distinctive social status. The matron, who will be assigned to them, will take responsibility for teaching the adolescent girls how to be good wives to their husbands and good mothers to their children.

This educational training can only be undertaken by youths who have attained puberty and upon the completion of this procedure, the initiated youths will be deemed ripe for marriage. Parents can never permit their son to take an uninitiated girl for a wife. In fact, the people’s culture considers uninitiated men and women as incomplete and they are treated despicably. Apart from preventing them from entering into the union of marriage, lack of initiation also stops such people from participating in the counsel of both men and women. They are deemed to be unfit for such activities since they are still kids. The worst part of it is that children of uninitiated parents can never become heirs to regal power in any place inhabited by the Tswana people.

Inheritance Rights Are Only Bestowed On Their Male Folks

The traditions of the Tswana people with regards to inheritance are predominantly patrilineal – inheritance can only be passed from father to his eldest son (it can also pass to any other legitimate or rightful male family successor). The younger sons are given smaller shares while the women have no right to inheritance.

When they need to till the land, women can only do so with the consent of their male folks as all landed properties are subject to male ownership. A deceased who died without male children will have his property inherited by the nearest male agnate.

Cultural Attires of The Tswana People

Batswana is known for wearing a cotton fabric called Leteisi in Setswana, and Shweshwe in Sotho. More often than not, this fabric is used for weddings or any other traditional celebrations. Gong by the traditions of the Setswanas during traditional baby-showers, mothers put on a checkered small blanket known as mogagolwane.

At initiation ceremonies and traditional wedding ceremonies, married women are identified with this adornment. They are also expected to wear mogagolwane during funerals.

Just like several other South African tribes, the unmarried young lady appears in beaded short skirts, beaded bras, head beads, beaded capes, and other accessories.

Important to note that prior to the arrival of the colonial masters, the Tswana people’s clothes were animal skin processed garments. The men put on tshega – a loin-skin coverage and kaross – an animal skin processed blanket. They also wear sandals, skin caps, and the warriors wore belts of tails.

Belief System of the Tswana People

The Tswana people are strong believers in the age-old African traditional religion and even though they were largely impacted by the coming of the Christian missionaries, a large population of the tribe still hold fast to their ancient gods.

Tswana Religion Is Centered Around The Supreme Being Modimo and the Ancestral Spirit Badimo

Supreme being Modimo takes the center stage in the religious belief of the Tswana people. Though it is not possible to sense Modimo directly, there is this strong belief that he alone is the very source and origin of all existence. Intangible, all-pervasive, ethereal, and irreparably part of human experience. Modimo is regarded as the custodian of the moral order. In times of affliction, he becomes the people’s source of appeal. The complexity of the tribe’s concept of this supreme being can be best specified by the plethora of praise names used in characterizing him.

Modimo is mme (this means “mother”) and lesedi (meaning “light”), however, this almighty being is equally known as selo (meaning “monster”) as he is also believed to be in possession of dangerous powers and influences that go far beyond what is expected normal humanity.

After the Modimo comes the Badimo which is the ancestral spirit (badimo is also used as the pluralized form of modimo). It is an honorific term used in expressing reverence and awe toward elders and toward the supreme being. This also serves as an indication that the dissimilarity between Modimo, the ancestral spirit, and people is one of degree as opposed to kind.

While they are believed to occupy diverse positions and ranks in a complex and multifaceted hierarchy of spiritual power, it is said that all beings—whether human or spiritual—are intimately linked with each other.

The Sacred Role Of The Badimos

According to the Tswana people, it is absolutely impossible for a human to have direct contact with the supreme being (modimo) and remain unchanged. Thus, the only option of contacting the Modimo is to go through the badimo – an intermediary between the supreme being and humanity. With that said, the badimo are the ones believed to be closely involved in the daily life and activities of the Tswana people. Below are some of the roles of the badimo

- The preservation of harmony in social relations

- They ensure fertility among the people, their crops, and animals.

- They display a parental attitude towards the people

- Correction of faults and the protections of their descendants from harm

- The welfare of the Tswana community as a whole is their key role.

In return for all these functions, the badimo expects tirelo (“service”) which essence is the common sharing of benefits. The badimo are believed to love company; they are especially delighted by feasts. Whenever the people prepare food or beer, the badimo gets a portion that will be poured on the ground. The essence of this is to maintain the good favor they enjoy with the ancestral spirit because in its absence, life can never be in proper balance and the people will not enjoy it to the full. Bolwetse (physical and spiritual sickness) will befall those that neglected to honor the ancestral spirit.

Seriti and The Badimo

Seriti (pl., diriti) is the theory of human personality according to the Tswana people. Each individual can be born with either a light or heavy seriti; this can either act for good or evil.

- Heavy seriti is believed to bring respect, dignity, and prosperity.

- A child who happens to be born with light seriti will need to have it strengthened and the family will try imbuing it with good intentions.

- Bad seriti brings about discord and ill will but when a chief or a head of household has good seriti, it will strengthen the diriti of people in the chiefdom or family and vise versa.

Categories of Religious Specialists (dingaka) Among the Tswana People

The spiritualists among the Tswana people are called dingaka (sg., ngaka ) and it is a career path open to both genders. The Tswanas have six kinds of doctors or spiritualists classified according to their medical skills and divinatory.

The “Horned” Doctors

He or she divines by the throwing of four tablets or pairs of astragalus bones. Four tablets represent an adult and younger male plus an older and younger female. Pairs of astragalus bones represent both males and females of all common animal species.

The “Hornless” Doctors

He or she divines by bodily examination of the patient.

Boloi Is a Kind Of Suffering That Comes From Sorcerers or If The Badimo is Displeased

Humans incur suffering or ailment through the activities of the sorcerers or when they incur the displeasure of the ancestral spirit, badimo. Both occurrences are brought under the term boloi which the Tswana people often translate as magic or sorcery. There are the socially constructive boloi and evil boloi.

The socially constructive boloi are of two types; the boloi of the mouth and that of the heart. Both involve offending an elder in your kin group who puts badimo on his offender. In turn, the badimo calls the offender’s attention to his fault by withdrawing their support from his seriti. Consequently, he is left susceptible to malign influences and ill health. The offender’s only option is to provide an animal which after slaughtering, the offended will strengthen back his seriti by washing him with a mixture of aloe and chyme.

The evil boloi are also two in number; Boloi ba bosigo (“night sorcery”) – this refers to witchcraft involving elderly women who work in covens and wreak havoc under the cloak of darkness. Like tricksters, they gather necked moving into houses through closed windows and doors to suck the milk from cows or nursing mothers, upset pots, exhume fresh corpses, use hyenas as steeds and owls as sentinels.

Day sorcery (boloi ba motshegare ) – this is a more serious sorcery involving the purposeful exploitation of material substances to achieve evil ends like inflicting people with disease or death. Sorcerer and their victims are usually related, like husband and wife, brother and brother who are overcome by greed, vengeance, or envy. The dingaka performs Bongaka, therapy for the prevention of sorcery.

Marriage Proceedings In The Tswana Tribe

As a people, the Tswana people have their own traditional marriage rites that must be properly observed before a union can be deemed legitimate. This usually starts from the betrothal process.

Betrothal Negotiations In the Tribe is Known As Patlo

According to the traditions of the Tswana people, the choice of a bride, including the ensuing betrothal, is the prerogative of the parents of the groom but most decisions come from his father and uncles. The tribe takes a girl’s consent for granted, parents don’t consult their daughters before making the choice of a husband for her and it is expected that she honors their choice. Generally, the process of betrothal negotiations is called patlo and the betrothed lady is called sego sa metsi’ – this means the one who will fetch water for the family’s domestic use. Both the terminology and process find expression in the purpose for which the wife was sought − to procreate as well as render domestic services to the family.

With the opening negotiations and agreements in place, a bride’s prospective husband will have the unquestionable right to visit her freely and even cohabit with her. However, this comes with serious implications in the event that a man terminates the relationship after siring children with the lady. The demand of the Tswana law under this circumstance is that the man should pay compensation for the terminated marriage prospects and maintain any child born from the union with six heads of cattle. The place of a betrothed bride who dies before marriage will be taken by her sister, this usually happens where bogadi has already exchanged hands.

Marriage and the Payment of Bogadi

After the formal betrothal comes the payment of the bride price which in the Tswana parlance is called bogadi. The concerned families are supposed to do the handing over of bogadi before the sun rises in the sky. In a demonstration of his manhood, the bridegroom is the one who will undertake the duty of driving cattle to his new in-law’s kraal where he will wait at the entrance as negations are ongoing on at the Kgotla. The negotiation taking place at this spot instead of the house is a symbolism of the masculine sphere of influence among the Tswana people.

After bogadi has exchanged hands, it confers on the groom considerable control and power over the bride. In the event that a woman fails to fulfill her obligations as required by tradition, a man who has already paid bogadi on her head has the right to freely chastise her. Upon the payment of bogadi, a woman’s productive and legal powers will be transferred to the family of her husband. In the event that the marriage ends in divorce or death, the payment of bogadi also limits the woman’s rights over her own children.

This is the reason why a man could call both children and wives, bana bame meaning my children. This practice is an indication of the man’s superiority as one who controls the family and the wives will always be subordinate to the husband and also his male relatives.

The payment of bogadi must always precede the marriage feast. Men who have acquired a lot of cattle can go ahead and marry more than one wife, increasing their chances of begetting more of the highly sought-after sons. Being an imperative requirement, the exchange of bogadi is what legalizes conjugal unions. The marriage feast marks the bride’s relocation from her birth family to the family of her husband. The choice of bogadi for the Tswana people has always been young cows or oxen but never bulls since bulls are regarded as a symbolism of male strength. Out of cows and oxen, the cows are preferable as the people believe it to be a symbolism of the reproductive ability of a woman.

Non-payment of Bogadi is Looked On With Disdain

It is true that the Tswana people allow a man who has completed the preliminary process of betrothal to visit or cohabit with his betrothed. However, once the man fails to produce bogadi, he will not be accorded any legal rights over any children that may come from the relationship. At the community level, such a man will lose his prestige and in addition, he will be under constant pressure by the parents of his betrothed to do the needful.

The consequences of non-payment of bogadi equally affect the would-be wife who will be treated as an object of shame. Marriage confers a rare kind of honor and prestige on women among the Tswana people and it will be really unfortunate for a woman whose intended groom fails to come up to scratch. For this reason, both bogadi and marriage are very attractive.

The payment of bogadi is no mean feat and is usually achieved through contributions from the groom’s father and uncles. When the groom gets settled as a man with his own herds of cattle, he will be expected to contribute to a relative’s bogadi in future. On the side of the woman’s family, the major benefactors of bridewealth are her maternal uncles, including their brothers.

Barrenness In Marriage is Only Traceable To Women In The Tswana Tribe

When a woman who is childless dies, the onus will be on her family to justify the payment of bogadi. This is usually achieved by replacing the deceased wife with a close relative which in several cases will be the sister. Just like several other tribes in the black continent of Africa, the Tswana people usually make no effort towards ascertaining the cause of bareness. The blame is automatically put on the woman who may even face charges of promiscuity before marriage.

Because of this practice, the social status of every Tswana woman is largely dependent on her fertility, though producing only female children is another negative situation entirely. The birth of male children is a crucial factor in the social identity and esteem of a man within the Tswana society.

In fact, the normal practice among the Tswana tribe is to look on a barren woman as a half-woman. Their reasons are that real women should be able to have children. Thus, any female who cannot fulfill this expectation is less of a woman.

Burial Ritual In The Tribe

Upon the death of a Motswana, the person’s relatives will leave no stones unturned in paying the last respect to their kinsman. The reason behind this effort is the ingrained belief that the dead become the badimo and continue to watch over the people. Even in present-day Tswana, the funeral parlor has become a thriving business as it is a way of showing respect to the deceased. The Tswana people start their pre-burial proceedings five days before the actual burial ceremony. During the five days, the family of the deceased erects a tent for all relatives to sleep in as the preparations are ongoing. They eat and drink all sorts of food and beverages, however, alcohol is strictly restricted during funerals. A mourner who slips out of the arena to secretly consume alcohol will be seen as one who disrespects the dead.

A Woman Must Sleep In The Room Of The Deceased Throughout The Burial Preparation

Once a person is declared dead, all the deceased clothes will be packed and placed next to a burning candle inside the room. The furniture in his room will be evacuated the next day, leaving only a mattress on the floor for a family member (elderly woman in the family) to sleep to keep the person’s spirit company. All these will be happening while the corpse is preserved in the funeral parlor. She will only leave the room to answer the call of nature (toilet) otherwise, all her food and drink will be served in the room.

On the day the corpse will be brought home for burial and placed in the room, the woman will be a silent onlooker while other family members enter the room to see the corpse for the last time. She will select just two dresses to wear during this period and on the day of the burial. She will be the chief demonstrator of the family’s grief with navy or black cloth and a matching kerchief tied on her head.

The Slaughtering of a Cow Is Significant In Tswana Burial

The tribe usually preserves their dead at a funeral parlor before the burial but once the corpse is brought home for burial, a cow will be slaughtered in the room with the dead body. According to the Tswana people, the spirit of the slaughtered cow will work towards protecting the deceased family against evil. The slaughtering is undertaken by the male folks while the women prepare and cook the meat. The cooking is done without herbs or spices, only salted water is allowed and they use cast-iron pots on an open fire.

If the deceased happens to be a female, they will slaughter a female cow for her burial and when it is a man, a male cow will be slaughtered. The hide will be neatly removed and used in wrapping the deceased for burial. However, though the modern-day Tswana now bury their dead in caskets, they still cover the corpse with the hide of the cow before putting it inside the casket.

The Burial Proper

They usually go to the graveyard in a long procession bearing the deceased with the women crying very loudly and persistently either to invite ancestor to the burial or scare the evil spirit away. After they have successfully buried the corpse, the funeral-goers will mix aloe with cold water and use it in washing their hands before they proceed to serve the food.

The Bathing of Direct Family Of The Deceased

Another important ritual occurs after burial when all the mourners must have gone home. The direct family of the deceased will gather before sunrise the next morning. Both the person’s spouse and children will have their hair completely shaved and they will stand in line naked to bath in a huge basin of cold water with the gall of the slaughtered cow thrown in. Also included in the water is the content of the cow’s intestine and Sebabetswana – an itchy substance from a wild plant. They are not allowed to dry their bodies before putting on their clothes and will not bathe again for the rest of the day.

The administrator of this bath is usually the deceased’s oldest brother who will also return in the next three months for a repeat performance. This time, they will kill either a goat or sheep and use the intestines and gall for the ritual bath. The meat is usually cooked and eaten. This bath ritual is meant to protect the direct family of the deceased from evil spirits during their morning period

Gender Roles Among The Tswana People

Peculiarly, agriculture is a woman’s domain in the Tswana tribe; the rites of passage into womanhood center around the soil’s fertility. Women are the major tillers of the soil and when their men folks manage to work in the farms, they take it as a way of helping their women.

On the flip side, cattle is associated with manliness, political power, and glory. The puberty rites of boys are shot through with the defense and care of cattle and even the titled men (the chiefs) come out to boast of their cattle-herding skills. Tswana women are debarred from entering a cattle pen and they cannot be allowed to milk the cows as that is the prerogative of the men.

The Batswana society has always regarded the place of women as inferior to their men counterparts. This can be witnessed at feasts and social gatherings where the men are given a far better reception than women. Spots like the Kgotla are an exclusive reserve for the men. A woman cannot show her face in the political arena only the men can be ordained as headmen and chiefs. Even in the economic production sphere, the division of labor between men and women is a well-defined one where the chores for women are treated as inferior.

The stage for political debates is no place for a woman, property acquisition and ownership was majorly a patrilineal affair, thus, the female folks were traditionally and historically excluded from the inheritance of any kind. Because of this practice, women among the Tswana people have remained economically dependent on their men.

Some of the duties of the men include:

- Going to war

- Hunting for game

- Watching the cattle

- Milking the cow

- Preparing cattle skins and furs for mantles

The chores allotted to women are the far heavier tasks which include

- Agriculture

- Building the houses

- Erecting fencing around the house

- Gathering firewood

- Rearing of a family

The Tswana People and Their Cuisine

Tswana tribes across Africa can boast of several nutritious edibles. Below are some of their major foods.

- Pap is one of their staple foods. Processed from corn, the food is often consumed with veggies and meat

- Bogobe is a special kind of bread processed with different types of flour

- Ting is the tribe’s most popular sorghum porridge

- Bogobe jwa Logala/Sengana – this meal is cooked using sorghum porridge with some milk thrown in.

- Seswaa – this comes in the form of shredded or pounded meat often served with Bogobe (a kind of porridge). Seswaa is a major food at funerals, weddings, and other celebrations.

- Processed from both goat and cow milk is Madila – sour cultured milk of the Tswana people. The preparation process for Madila takes a while before it can be deemed mature enough for consumption. The Lekuka, which can also come in the form of a leather bag or sack, is used in the processing of Madila and can also be used for its storage. Usually, the Tswana tribe would use Madila as relish consumed with pap. The people also use it in their popular breakfast meal, motogo, as it gives the soft porridge a milky and sour taste.

- The number of edibles consumed by the members of the tribe extends to include some forest food like moretlwa (wild berries grewia flava). The people can preserve this berry by drying and storing them to be used in the future. Moretlwa is majorly used in the making of a local beer known as khadi.

- The women of Tswana are also known for gathering several other edible fruits and roots – a good example is the fruits from morula tree – this also goes into the makings of various kinds of drinks

- Women who often go scavenging in the forest normally gather wild greens– this serves as a supplement to their normal day-to-day diets.

The Tswana People Love To Perform Music

The tribe is known for their traditional music which is majorly vocal and performed without the use of instruments at times. However, this is dependent on the caliber of the occasion. Their folk music equally uses string instruments when the occasion calls for it. Some of their instruments include:

- Setinkane – this is a Botswana version of the mini piano

- Segankure/Segaba – Segankure/Segaba happens to be a Botswana version of the Erhu which is a Chinese instrument

- Moropa (Meropa -plural) – this one is a Botswana version of several arrays of drums

- Phala – a Botswana version of a whistle That is majorly used during celebrations; it comes in a plethora of forms.

Musical instruments among the Tswana people are not restricted to drums, strings, and the likes as the people also employ their hands as musical instruments. They make harmonious sounds by clapping the two hands together but on the other hand, they can wrap a goatskin turned upside down around their calf and use their hands to clap against it. It is only the males that are privileged to create rhythm and music with the goatskin.

In recent times, the Tswana tribe has started using the guitar as a flexible musical instrument as it has proved to be far better than the Segaba in offering a variety of strings. Motswako is another of the people’s notable modern music which comes in the form of Tswana Rap.

Some of the people’s forms of artistic expression include pina-song and pino – dance. On both ritual and official occasions, competitions and performances are organized for their choirs. Their pina is usually a composition of lyrics offering narratives as well as critiques of both the present and the past.

The Tswana People are Noted For Their visual Arts

Visual arts objects made by members of this distinguished tribe runs to baskets, clay pots, cooking utensils, and the likes. The people use Mokola Palm and local dyes in processing their baskets which are realized as beautiful craftwork. They generally weave their baskets into three notable types;

- The large open baskets used – for winnowing threshed grain or for carrying things on the head

- Large lidded baskets – for storage purposes

- Smaller plates – used for winnowing pounded grain.

The clay pot made by potters comes in handy for storing water as well as their traditional beer. They can also suffice as cooking pots but never for commercial purposes.

Wooden crafts and traditional cooking utensils like leso and lehetlho are the handiwork of craft makers. They are also responsible for producing their traditional wooden chair as well as drums. The beautiful designs on the people’s houses is another form of visual art from the Tswana people.