The Swazi people of Africa are those that belong to Nguni clans who speak the Nguni language siSwati which is traceable to East Africa. The people are very rich in cultural heritage with different distinguished ceremonies like the Umhlanga, the Umchwasho, and the Incwala. Swazi people are strong believers in the traditional religion of ancient times, where the ancestors act as intermediaries between the living and the dead.

Even with the advent of Christianity, the people still hold fast to their traditional religious beliefs. However, some extreme forms of their religion like using human parts in the preparation of medicine have long become a thing of the past. This is just a scratch on the surface as there is a whole lot more about the culture, beliefs, and traditions of the Swazi.

History of the Swazi People

In South Africa, the Swazi people are a Bantu ethnic group that inhabit the sovereign kingdom in the country known as Eswatini. The Emaswati belong to the Nguni-language speakers whose roots are traceable to East Africa where there is evidence of similar culture, beliefs, and traditions. In the 15th century, the EmaSwati put down temporary roots in southeast Africa following a major migration from north East Africa.

Moving into southern Mozambique, they later found their way to their present settlement, Eswatini, which had the San people in residence at that time.

The term EmaSwati can be used interchangeably with bakaNgwane (meaning “Ngwane’s people”). We must acknowledge the fact that there are some Swati people whose origins are traceable to Sotho clans – these people can be found in the present-day Eswatini.

Breaking new frontiers southwards under the Nguni expansion during the later part of the late fifteenth century, the Swati people passed through Limpopo River to a settlement in southern Tongaland (presently southern Mozambique close to Maputo).

For the Ngwane people, history said they moved into the present Eswatini territory around 1600. This happened after Dlamini III took over the reins of power from Maseko; Dlamini III was the one who led his people into Eswatini in 1750, settling along Pongola River at the point where the body of water cuts right through the Lubombo Mountains.

They later relocated to another part of the Pongola River, closer to the Ndwandwe people. Ngwane III succeeded Dlamini III and is today regarded as modern Eswatini’s first king. His rule prevailed at the Shiselweni part of Eswatini from 1745 to 1780.

Expansion of the Kingdom By Conquering

Sobhuza I began to wield the big stick in Eswatini in 1815 and as the king, he undertook the founding and establishment of Swati power within central Eswatini. Following this, the Emaswati continued their expansion process by conquering several small Sotho and Nguni-speaking tribes. This was what led to the building of the large composite state presently known as Eswatini.

It was during the Mfecane that Sobhuza I reigned and under his leadership, other tribes like the Sotho, the Nguni, and a few remaining San groups became part of the Swazi nation by integration. This was also when Eswatini‘s present boundaries were ruled by the Dlamini kings.

Towards the concluding part of the 1830s, the Boers (the emerged winner at the Battle of Blood River with the Zulus) had contact with Swati people while putting down roots in the territory that became the present-day South African Republic. As the Transvaal Boers settled in the region of the Lydenburg during the 1840s, a large chunk of Swati territory was surrendered to them.

The then king of Eswatini, Mswati II, earned recognition from both the British and the Transvaal, and it was during Mswati II’s reign that the Swazi nation finally became unified. Thus, from then on, the label “Swati” was eventually applied to all who paid allegiance/loyalty to the Ingwenyama.

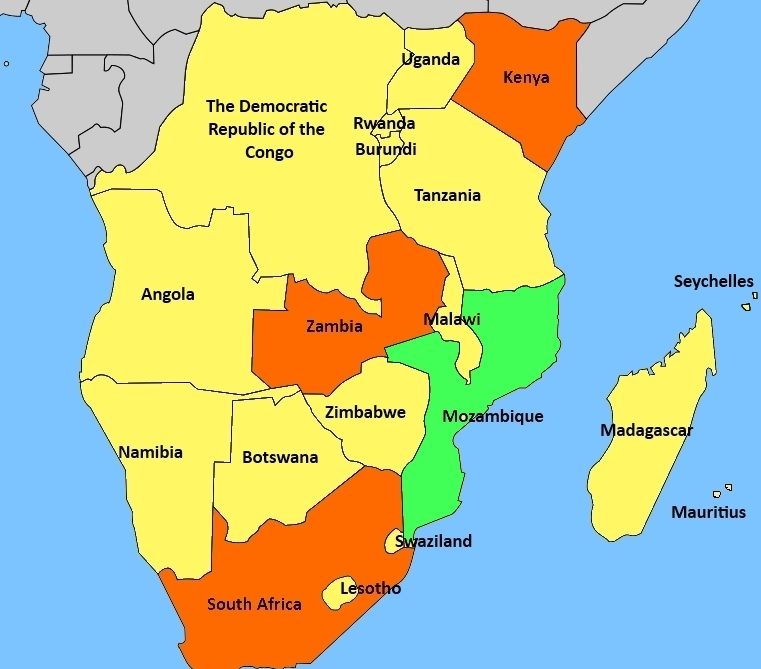

Geographical Distribution

The Swazi people lost so much land to South Africa after the Boer settlers and the British laid claims to land and mining concessions which led so many members of the tribe to live outside Eswatini. In 1903, Britain claimed authority over their land but independence was regained in 1968.

Presently, we see so many Swati people residing in both Eswatini and South Africa where they can be easily identified with their SiSwati dialect and language. EmaSwati in Eswatini is lesser in number compared to EmaSwati in South Africa at 1.2 million. There is a minor three percent of this population called “White Swazi” which is made up of Europeans.

Linguistic Affiliation Of The Swati People

Swazi is the name of the ethnic group, tribe, or nation, and the language spoken by the people is called siSwati. Speakers of the “siSwati” language abound in South Africa, Swaziland, and Mozambique. Belonging to the Nguni subgroup, siSwati is classified as a Southern Bantu language. The language has a close relationship with the Zulu and a distant one with the Xhosa.

So far, there have not been any known publications in siSwati. The language can also be referred to as Swati, Swazi, Sewati, or siSwati, and it is recognized in South Africa as one of its official languages.

The Swati Clans

As a nation, the Swati people were originally formed by a total of 16 different clans called bemdzabuko (“true Swazi”). These people accompanied the Dlamini kings when the Royal bloodline of Dlamini settled in the neighborhood of Delagoa Bay during ancient times. The true Swazi has 15 founding clans, including:

- Dlamini

- Nhlabath

- Hlophe

- Kunene

- Mabuza

- Madvonsela

- Mamba

- Matsebula

- Mdluli

- Motsa

- Ngwenya

- Shongwe

- Sukati

- Tsabedze

- Tfwala

- Zwane.

In addition to the afore listed, there are still other clans of the Swazi people called the Emakhandzambili clans (meaning “those found ahead”). They include:

- Gamedze

- Fakudze

- Ngcamphalala

- Magagula

The term Emakhandzambili means that these people were already settled on the land before the immigration and conquest by Dlamini.

There still exists a third set of clans called The Emafikemuva (meaning, “those who came behind”). These are the ones that joined the kingdom much later.

Kin Groups

The major kin group among the Swazi people is the clan. The surname of a Swazi is the clan name of their father. Even after marriage, a Swazi woman would still retain membership of her paternal clan. However, the common practice is for married women to bear their spouse’s clan name as a surname.

Social Stratification

Between the residents of the urban and rural communities, there is this sharp social division that is a reflection of the emergence of the middle class. The Swati people rank clans according to the kind of relationship they share with the king.

With that said, the royal clan known as the Nkosi Dlamini clan happens to occupy the top position on the ranking list. Coming next in line is a group of clans described by tradition as “Bearers of Kings” (these are the clans where queen mothers have come from). The role of the queen’s mother is to serve as some sort of check on the king’s powers. Once a royal heir is selected, his mother automatically becomes the next mother of the king.

Culture

Among the Swazi people, culture is regarded as a way of life and these customs and traditions have undergone historical stages. The tribe’s culture involves a lot of things such as music, rites of passage, inheritance, marriage, and a whole lot more

National cultural events abound, including the likes of umhlanga, incwala, and emaganu usually hosted at the Ngwenyama and Ndlovukati’s Royal residences.

What of the imiphakatsi (local cultural events within the communities) that takes place at the emphakatsini’s (chief) residence.

Funerals, religious events, and weddings occur at the homesteads of the concerned families where the family members, friends, and neighbors partake in the occasion

Rites of Passage

When Swazi children are still in infancy age, they will be engaged with daily activities like running errands within the homestead. As they grow older, preferably at age six, tradition separates them, boys will start learning the rudiments of cattle rearing with their mates. They also need to be hardened to face public life. On the other hand, the girls will be expected to lend a hand with domestic activities including child-rearing. Child-rearing is the prerogative of mothers as fathers have very little or no impute into raising children.

As puberty downs, boys will be tended by traditional healers, eventually joining the warriors of his age (libutfo) to learn important activities like service to the king, including facts about manhood. Girls on the other hand will wait to see their first menstruation before they will be acknowledged. Following this, they will go into isolation, staying days in a hut where their mothers will play the role of instructors, teaching them about taboos and observances

The last time Swazi people circumcised males was during the reign of King Mswati around the middle of the 19th century. However, tradition demands that adolescent boys and girls will undergo ukusika tindlebe (having their ears cut)

Marriage In The Swazi Culture

After puberty and the completion of the initiation process for both boys and girls, they will be deemed ready to embrace matrimony. This is when marriage negotiations begin between two consenting families.

After negotiations, Umtsimba (Swazi traditional marriage) follows. The Umtsimba is where a new wife will hand herself over to her spouse’s family for the remaining part of her life. It is a big celebration involving both families and it comes in stages stretching over a few days.

All the stages of the Umtsimba are highly significant suffused with gestures and symbolically passed on from one generation to another. It is normally scheduled during the dry season (between June and August) and must begin during the weekend, preferably, Friday night

- The first stage involves extensive preparations that will be made by the bridal party before they take off from the bride’s home to the groom’s homestead. This usually occurs on Friday evening.

- The second stage of the Umtsimba is observed during the bridal party’s journey as they move from their village to the village of their in-laws

- The first day of the Umtsimba marks the third stage and it usually spans three days, beginning upon the arrival of the bridal party at the village of the groom.

- Following this, the actual marriage ceremony occurs – (this happens to be the fourth stage)

- The fifth stage is called the kuteka (this is referred to as “the actual wedding”) and occurs the day after the ceremony

- Then comes the final stage when the bride is expected to present gifts to her new family. This is equally the first time the bride will be spending an evening with her the groom.

All these afore listed stages are marked with different types of activities

- Saturday morning is when the bridal party relaxes by any river in the vicinity to eat both cow and goat meat presented by the groom’s family.

- They will dance in the homestead of the groom in the afternoon.

- As Sunday morning dawns, the bride, alongside her female relatives will move to the groom’s cattle kraal to stab the ground with a spear.

The high point of Umtsimba among the Swati people is when the new bride will be smeared with red ochre; This is a very important process as no single woman will get to be smeared two times

Types of Marriages

In contemporary Swazi culture, several forms of marriage exist

- There is the customary marriage that can come in the form of “love” marriage

- The ukwendzisa is the arranged marriage

- There is also the bride-capture marriage which is not common. While all the other forms of marriages may involve the payment of bride-wealth, the bride-capture marriage will not.

- Sororate is where a woman gets married to the husband of her sister; this makes her the subsidiary wife called inhlanti in the Swati people’s parlance.

- Polygynous marriages where a man takes more than one woman as wives were once common. However, economic considerations and Christianity have reduced the practice of plurality in marriage.

- The one that is most common among Christians in the present-day Swazi is Christian marriage.

Rules of Marriage

- The payment of bridal wealth (lobola) gives a man and his family the rights to children

- Lobala was previously paid with heads of cattle, but in recent times cash is involved

- People who belong to the same clan are forbidden to intermarry, though marriage can be facilitated between people in the same clan by the occasional creation of subclans.

Domestic Unit

Traditionally, the norm in the rural areas of the Swati people is a patrilocal residence and a typical homestead comprises of the headman, his wife/wives, married sons with their own nuclear family, and unmarried siblings. The minor children excluded, every other female in the homestead is seen as an outsider whose economic values are measurable in Lobola; The bridewealth usually comes in the form of cattle. While they calculate the value of their female folks in terms of cattle, the Swazi place very high value on their sone

The umuti (homestead) is headed by an umnumzana assisted by his wife (the head wife in the case of polygamous marriage). Among co-wives, the head wife is determined by clan memberships as opposed to the order of marriage. The umnumzana takes major decisions on things like

- Resource allocation

- Land distribution

- Production (plowing including the types of crops grown)

- Economic expenditures

- The mobilization of homestead labor.

Individual residents in a homestead have access to arable land. As members of a community, they are eligible to access communal pasturage.

A complex homestead would have households called indlu consisting of a nuclear family where members eat from the same kitchen and share agricultural tasks. Sometimes, an inhlanti (an attached co-wife) will form part of an indlu alongside her own children.

As sons get married, they move to form another indlu within their mother’s wider house.

The Swati people don’t furnish their indlu with beds and chairs, the inhabitants sleep and sit on grass mats. Women are expected to cook on open fires in homesteads that lack stoves. The utensil used by the people is usually homemade. Residents of each homestead display resourcefulness in accomplishing tasks. A good instance is in the way women clean earthen floors; they just smear them with moistened cow dung leaving the floors smooth and smelling sweet

Nguni Huts

The structure in which the ancient Swazi live is called Nguni huts and many still reside in these traditional huts. These huts are constructed with local building materials such as poles and thatch bounded with ropes. The Nguni huts are not just for residential purposes, they are also of great significance in the tribe. There is the indlunkulu hut used as a shrine. Also, there are special huts meant for wives in a homestead

Socialization Among the Swati People

According to the traditions of the Swati people, infants won’t be recognized as “persons” till they get to their third month of life. Prior to their third month, anybody that wants to refer to them will call them things” At this stage, the baby is not entitled to a name and men cannot even touch it.

After the newborn attains the status of “personhood” at three months, it will get a name but will continue to stay with the mother who carries it in a back sling. The baby will be weaned from the mother’s breast at age two or three.

After weaning at the age of three, the baby will come out from the protection of the mother and start associating with peers. At this stage, the mother is free to leave the child in the care of older children in the homestead and with time, discipline will be introduced. Children learn by “playing house “and imitating the adults

Gender Roles and Statuses

In the traditional Swazi setting, work is divided according to criteria such as sex, pedigree, and age

Men

Cattle herding is the exclusive domain of men as cattle have very important symbolic and economic value. The construction of residential houses and structures used as cattle kraals (corrals) is the work of the male folks. They also undertake duties like plowing, tending, and milking cattle, sewing skins, and cutting shields.

There are men who are particularly proficient and accomplished at warfare, hunting, animal husbandry, and governing

Women

It is the duty of women to hoe, plant crops, as well as harvest them. They are allowed to tend small livestock in addition to caring for the children.

They take charge of duties like thatching, plaiting of ropes, weaving of mats and baskets, grinding of grain, beer brewing, and also cook foods for their families.

There are some women who display proficiency in pottery and other forms of art.

The area of agriculture is one place where men corporate with women. The husbands gift their wives with gardens for cultivation.

Age comes to play when it is time to determine who performs which task, especially those that have to do with ritual performances. Rank is highly important in determining whose right it is to summon the people for work as well as who will take charge of supervising them.

Inheritance

When the umnumzana (head of the homestead) dies, his family council of agnates (this encompasses his full and half-brothers, his own senior sons and the senior sons of his brothers, etc) will converge to discuss how the deceased property and estate will be disposed of. What the council will consider include the household divisions existing within the dead head’s homestead during his lifetime, including all the land allocations he made.

The oldest son gets the largest land allocation plus administrative responsibilities in monogamous families. However, this privilege goes to the senior wife’s oldest son in polygynous families. He will also be named as the inkosana (general heir) and undertake the duty of acting as guardian over the heirs of each of the wife’s house’s estate. There are instances where they will have to appoint the heir after the demise of the father, especially where the eldest son will not emerge as the main heir. Important to note that, the order of marriage does not confer the status of senior wife to a woman. Thus, the rank of a man’s mother will come to play in choosing who will be the main heir

Cattles and landed properties can only be inherited by the men folks. A deceased woman will only have properties like mats, pots, and other utensils, and by tradition, it is her eldest son’s wife that will inherit them. The reason is that the daughter-in-law is part of the same homestead, unlike the woman’s daughters who have all married and live in their husband’s homes.

Death and the Afterlife

After death, corpses are subjected to some mortuary rituals; this varies depending on the status of the deceased. Also to be taken into consideration is the deceased relationship with the people left behind to mourn his or her death. A very important man would attract elaborate funeral rites while a mere common or a poor man would not attract such. A king’s burial is the most elaborate you can get within the Swazi enclave. When the head of any household dies, his burial place must be at the sibaya.

During burials, those who have close blood ties with the deceased are the ones expected to be the chief mourners. Their ritualized display of grief is expected to attract attention.

After a man has been buried, his widow gets her head shaved and commences the mourning period which lasts for a long time. A widow may decide to continue his lineage through ngena – a levirate marriage where the woman gets married to the deceased husband’s male relative and gets children on his behalf. However, the ngena is no longer as common as it used to be in the olden days.

According to the mythology of the Swati people, the spirit of the dead has a distinct existence. These ancestral spirits may possibly manifest in omens, in various forms of sicknesses, in the form of snakes, and many more.

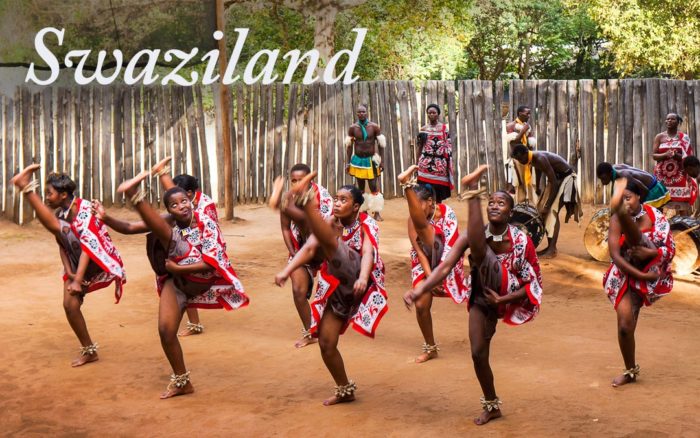

Music

The Swazi people can lay claims to a rich tradition of both music and dance completely untouched by Western influence. Their music is unique but they have adopted a few from neighboring tribes. A good example is the siBhaca recreational dance adopted from the Xhosas.

Swazi women make their weeding and digging work go faster by singing in groups as they work. While paying homage to royalty, the men also sing together. Celebrants at weddings, coming-of-age, royal rituals, and national Independence Day festivities also perform special songs. Swazi people can boast of praise-poets who are famous in the whole of South Africa – these people are renowned for composing praise poems for royalty such as kings, chiefs including prominent people.

Popular dancing and singing are accompanied by musical instruments crafted by Swazi specialists. Some of the ancient musical instruments of the tribe include

- The luvene (a hunting horn)

- Impalampala (a kudu bull horn)

- Ligubhu and makhweyane (this is in the form of a calabash with a wooden bow attached to it)

- Livenge (a plant-processed wind instrument).

Some of these musical instruments are still in use today and the Swazi people also produce music with drums, including European instruments.

Major Ceremonies Among the Swati People

The tribe celebrate different kinds of ceremonies for coming of age, harvest, marriage, burial, and the likes

1. Umhlanga

Among Eswatini’s best-known cultural practices is the Umhlanga. This event is targeted at nubile young girls and held annually between the months of August and September when the adolescent girls pay homage to their Ndlovukati

The Umhlanga Reed Dance is not a one-day event as it lasts for eight days. The girls will go to the Queen mother with reeds which they will present before her and then dance to the rhythm of the reed dance (this is not any form of competition).

It is a known fact that the dance is the exclusive right of unmarried girls, however, single girls who have had children out of wedlock will be disqualified. The aim of the reed dance is the preservation of the chastity of young girls. They also leverage it for providing the queen mother with tribute labor and it is a way of encouraging them by coming together to work.

It is the duty of the royal family to appoint an “induna” (a commoner maiden that will function as captain for the ceremony). Once chosen, the onus is now on the “induna” to make a general announcement, relating the chosen dates for the event. Important to mention that anybody cannot be an “induna”; there are laid down criteria for choosing the maiden that will perfectly fit that bill

- An “induna” must be someone who is very knowledgeable on royal protocol

- The young lady must be an expert at dancing

- The “induna” will not work alone as she will have one of the king’s daughters as her counterpart

2. Umchwasho

The Umhlanga Reed Dance observed by the Swati people of today isn’t an ancient ceremony, rather, it is a more modern version of the olden days “umchwasho” custom. During the period for the “umchwasho” all nubile young girls will be assigned to a female age-regiment

When an unmarried girl gets in the family way, her family will be fined with one cow which will be presented to their village chief. The qualified girls will spend some years in “umchwasho” until they are deemed to have attained marriageable age. This is when they will come out to meet the queen for the performance of labor service. It was a big ceremony that involved a lot of feasting and dancing. Until the 19th of August 2005, Swati people were under the chastity ritual of “umchwasho”

3. Incwala

The Incwala happens to be Eswatini’s most important cultural ceremony/event. The Swati people take the phases of the moon into consideration before fixing a date for Incwala and it might fall anytime between December and January. Also called the ceremony of the “First Fruits” (the English translation), the Incwala marks the day the king will get to taste the new harvest.

The Incwala ceremony goes with the King, there won’t be any Incwala without a king. Getting an ordinary chief or commoner to host the Incwala is viewed as treason among the tribe. These are the dignitaries expected to be present at Incwala.

- The King

- Queen Mother

- Royal wives and children

- The royal governors (the indunas),

- The chiefs

- The regiments

- The “bemanti” or “the water people”

Religion

The Swazi culture believes in the existence of a supreme being known as Mkhulumnqande. According to the tribe’s mythology, the earth was formed by Mkhulumnqande who demands no sacrifice. Mkhulumnqande isn’t associated with the ancestral spirits nor is it worshiped alongside the ancestors. During the tribe’s traditional religious ceremonies, it is the men that make sacrifices to the ancestral spirits.

Mvelincanti (means he who was present from the beginning), and is the tribe’s name for the creator. The women on the other hand can communicate with the spirits. In addition, it is the prerogative of the Queen mother to function as the custodian/caretaker of the rain medicines.

Most Swati people now practice Christianity, however, a large percentage of them still hold fast to the religion of their ancestors. For the ones that actually profess to be practicing Christianity, they didn’t completely jettison their traditional religion, they just blend the Christian tenets with their traditional spiritual beliefs

The Tinyanga

The Swati people perform spiritual rituals at the family level, and these can be seen at births, marriages, and deaths. People who are sick, possessed, or ailed with bad luck consult the traditional healers known as tinyanga who heals with the aid of rituals and natural medicine. The Swati people are strong believers in sorcery and witchcraft. There is also the “Muti (medicine) murders” which entails the killing of human beings and using their body parts to prepare powerful medicine. This kind of medicine is only demanded under very serious ailments that may result in the death of the sick person.

The Inyanga is the equivalent of a medical and pharmaceutical specialist, however, in the parlance of the Swazi, the Inyanga determines the root cause of an ailment through his bone-throwing skills.

The Sangoma

The traditional diviners among the swat people are called Sangoma or tangoma. According to the beliefs of the tribe, the tangoma is far more powerful, compared to the healers. The diviners are typically male and more often than not, they are possessed by spirits. The selection of the Sangoma is carried out by the ancestors of a particular family. When someone is appointed as a Sangoma, the person will undergo a special training known as “kwetfwasa”.

The end of the “kwetfwasa” heralds a graduation ceremony involving all Sangoma in the locality who will converge for feasting and dancing. The work of the diviner is divination and he diagnoses the sick based on what is known as “kubhula”. “kubhula” is a communication process, through trance/spell, with the natural super-powers.

Food and Economy

Traditional food supply for the Swati people fluctuates seasonally from winter to summer and the people experience periods of shortages. Their chief agricultural products include the likes of sugarcane, maize, cotton, tobacco, citrus fruits, rice, pineapples, sorghum, corn, and peanuts – these are mainly for commercial purposes.

Most of the foodstuff they cultivate solely for consumption include maize, beans, sorghum, sweet potatoes, and groundnuts. The tribe’s main staples are millet and maize, children get the dairy products like soured milk, and the traditional diet is completed with leafy vegetables, fruits, and roots. The slaughtering of cattle is majorly for ritual purposes, keeping meat in short supply.

For the people’s primary food which is Mealie-meal (comes in the form of ground maize), it is eaten alongside meat and wild veggies. The meat can be beef which is slaughtered for festive occasions and chicken for ordinary times. A special occasion may also call for the brewing of the traditional Swazi beer

Animal Husbandry

When it comes to the rearing of animals, the key focus of the Swati people is usually cattle. Cattle rearing is the job of the men folks who have their cattle kraals attached to their different homesteads. Cattle is a mark of prestige and the number of cows you have in your kraal determines your status in Swazi society.

Apart from cattle rearing, the Swazi people also engage in the rearing of smaller livestock like goats and sheep. They also have poultries for the supply of chicken and eggs

Mode of Eating

The Swazi use plastic, metal, or ceramic dishware for eating. Many who would prefer going by the customary practice of the tribe used a carved wooden bowl for serving meat and a black clay pot for drinking their traditional beer.

Families enjoy eating from the same bowl or plate, same can be said for age mates and friends who enjoy eating together. The best utensil for eating in the tribe is the fingers, people use their fingers to scoop the food out of the bowl and into their mouths.

Food Taboo

The Swati people are one African tribe that observes a lot of food taboos. Notable among these forbidden foods is fish. Though the Swati people do consume eggs, females (this includes the girl child and older women) are not allowed to eat them. A Swazi female consuming egg is declared unthinkable.

While everybody can consume dairy products, it is deemed taboo for wives to take them. The general food taboo of the Swati people notwithstanding, some specific clans within the tribe also observe their own food taboos. Many clans prohibit the consumption of particular wild animals, including birds.

Exportation

Various commercial and agricultural products now serve as sources of revenue in contemporary Swaziland. The country produces a lot of commercial agric products but the major ones are sugar produced from irrigated cane, maize, tobacco, vegetables, rice, cotton, citrus fruits, and pineapples.

Most of these cash crops are traded within the country and the majority of them are shipped outside Swaziland through exportation. The major ones that go outside the country are sugar, Soft drink concentrates, cotton yarn, and wood pulp.

What of the country’s mineral wealth that consists of iron ore, diamonds, coal, and asbestos; all these are mined for export outside Swaziland. A majority of Swaziland’s export goods end up in South Africa but 20 percent of it get to the European Union

At Matsapha, there is an industrial estate that produces processed forestry and agricultural products, textiles, garments, and several light manufactured goods.

Traditional Attire of the Swazi

The traditional attires of the Swati people vary depending on variables like gender, age, financial status, and a lot more. In this tribe, infants aged three months and below are not entitled to any form of clothing. All they need at that stage is protective medicine and nothing more.

Traditional Clothing For Swazi Men

Men in Swaziland put on colorful skirt-like cloth covers with a hide apron known as emajobo. During ceremonial occasions, the emajobo will be further adorned with a lot of ornamental items.

The menfolk also wears other adornments like a neckband called ligcebesha and ties known as umgaco Their other ornamental paraphernalia include a sagibo which comes in the form of a walking stick. The limb ornaments, siphandle complete the men’s attire for commoners. Royalty would normally use red feathers known as ligwalagwala.

Men’s Clothing According to Age

- From three months to three years – boys wear tiny loin skin.

- Between three to eight years – boys put on loin skin

- From eight to 17 years is when the adolescent men will be eligible to put on a penis cap alongside their loin skin.

- Unmarried men must wear loin skins, cloth, including bead ornaments

- A man that just got married wear loin skins

Traditional Clothing For Swazi Women

Swazi traditional apparel for women is called the ilihhiya (cloth). For married women, their upper torso must be covered and they make hair in the traditional “beehive” hairdo.

The unmarried ladies would normally adorn their upper torso with colorful beads during special occasions like the Reed Dance they perform for the Queen mother during their coming of age.

Women’s Clothing According to Age

- From three months to three years – girls may not wear any clothes at all, however, a string of multicolored beads may be worn on special occasions.

- Between three to eight years – girls wear fabric or grass-processed skirt alongside some beaded work

- Girls between eight to 15 must wear a grass-processed skirt alongside a short toga of fabric. They must always wear a beaded necklace.

- Females of marriageable age must put on a dress of fabric, putting their hair up to form a small bun

- New wives put on skin skirts, skin aprons, plus another apron under their armpits

Arts and Craft

Crop cultivation and animal husbandry were not the only means of sustenance for the Swati people as they were deeply involved in arts and crafts.

The Eswatini were renowned for pottery; some of their items include

- Clay pots (tindziwo); they are used for fetching water, cooking and preparing their local beer, and for decorations around the house.

- They were experts in carving wooden sculptures that came in handy as utensils. An apt example is the umcwembe that the people used for serving meat

- The people’s handcraft industry extends to include grass-processed items such as emacansi and tihlantsi (grass mats)

- They also made items like baskets, brooms, and many more.

- Their clothing items and jewelry were quite unique as most of them were processed from colorful beads. A good instance is the ligcebesha (colorful beaded necklace) and the indlamu (a colorful beaded skirt worn by young girls)